Mystery of Supersonic Turbulence Solved

5 November 2024

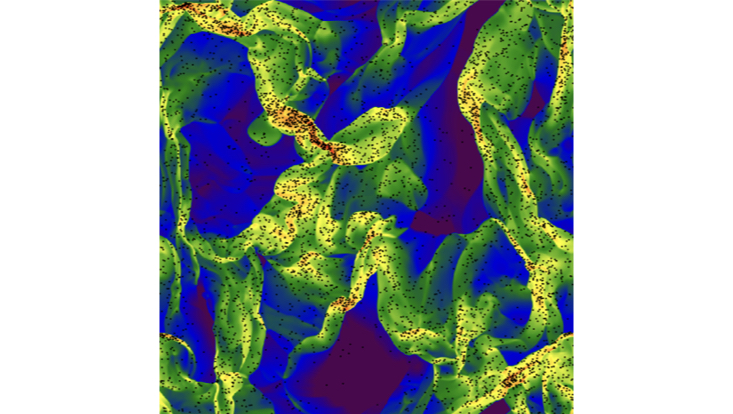

Photo: Evan Scannapieco et al. (2024)

Which clumps of interstellar gas will collapse under gravity to form stars and which clumps will not? This is related to a key problem in turbulence: to understand the distribution of densities produced. Using simulations and analytic work, researchers have been able to both track and model the evolution of densities under supersonic turbulence, recently published in the journal Science Advances.

On an aeroplane, movements of the air on small and large scales around the plane contribute to turbulence that can lead to a bumpy flight. Turbulence on a much larger scale is important for the formation of stars in giant molecular clouds that criss-cross the Milky Way.

In their new study, an international team of scientists, including the Excellence Cluster Quantum Universe, created simulations on supercomputers to study how turbulence changes the density of the interstellar gaseous medium. This is important, for example, in the formation of stars, as high-density clumps are the places where new stars are born. Our Sun, for example, formed 4.6 billion years ago in such a dense clump.

‘We know that the main process that determines when and how fast stars form is turbulence, because it creates the structures from which stars are formed,’ says Marcus Brüggen, Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Hamburg and principal investigator in the Excellence Cluster. ‘Our study reveals how these structures are formed.’

The team, with co-authors from the USA and China, found that the acceleration and deceleration of shocks plays a significant role in how many very dense regions exist in such a turbulent medium. Shocks slow down when they penetrate high-density gas and speed up when they penetrate low-density gas. This is analogous to the amplification of an ocean wave when it encounters shallow water near the shore. Using methods from statistical physics and computer simulations, they were able to explain for the first time how dense regions form in turbulent gas.

When a particle encounters a shock, the area around it becomes denser and denser. However, since shocks slow down in dense regions, turbulent motions can no longer compress the clumps once they are dense enough. These clumpy, high-density regions are the places where stars are most likely to form.

‘Now we can better understand why these structures look the way they do because we are able to trace their history,’ says Brüggen.