Observing collider neutrinos with FASER

17 May 2024

Photo: Yuki Akimoto@higgstan.com

Although particle collider experiments are known to produce an enormous number of neutrinos, these have never been observed directly. This situation has recently changed: scientists working on the ForwArd Search ExpeRiment (FASER) have reported the first detection of neutrinos from a particle collider. This groundbreaking achievement marks the beginning of an era of neutrino physics at particle colliders that will provide new avenues for studying fundamental physics at the highest human-made energies.

Neutrinos are among the most abundant particles in the Universe. However, despite their abundance they usually escape our attention since they interact only very rarely with matter. In fact, trillions of them pass through our bodies every second, yet most of us will never experience even a single interaction with these elusive particles.

Nevertheless, scientists have found ways to study these elusive particles. This typically involves high-intensity neutrino sources and huge detectors that can overcome the rarity of neutrino interactions. This way, researchers were able to observe neutrinos originating from various natural phenomena, such as the Earth, the Sun or even far away supernovae, as well as artificial sources like nuclear reactors and particle accelerators. Each of these observations has provided new insights for various fields, including particle physics, geophysics and astrophysics.

But how do scientists manage to catch these elusive neutrinos? Since neutrinos are neutral particles, they can't be directly observed by conventional detectors. Instead, scientists rely on the particles generated when neutrinos interact with matter. By studying the properties of these interaction products, researchers can infer that a neutrino was present and even extract valuable information about the neutrinos themselves.

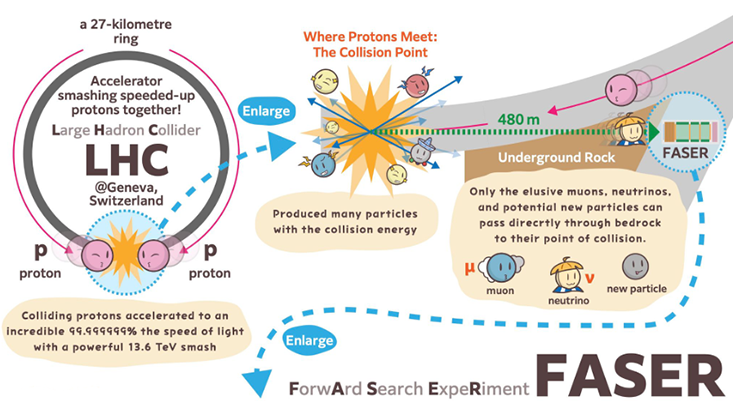

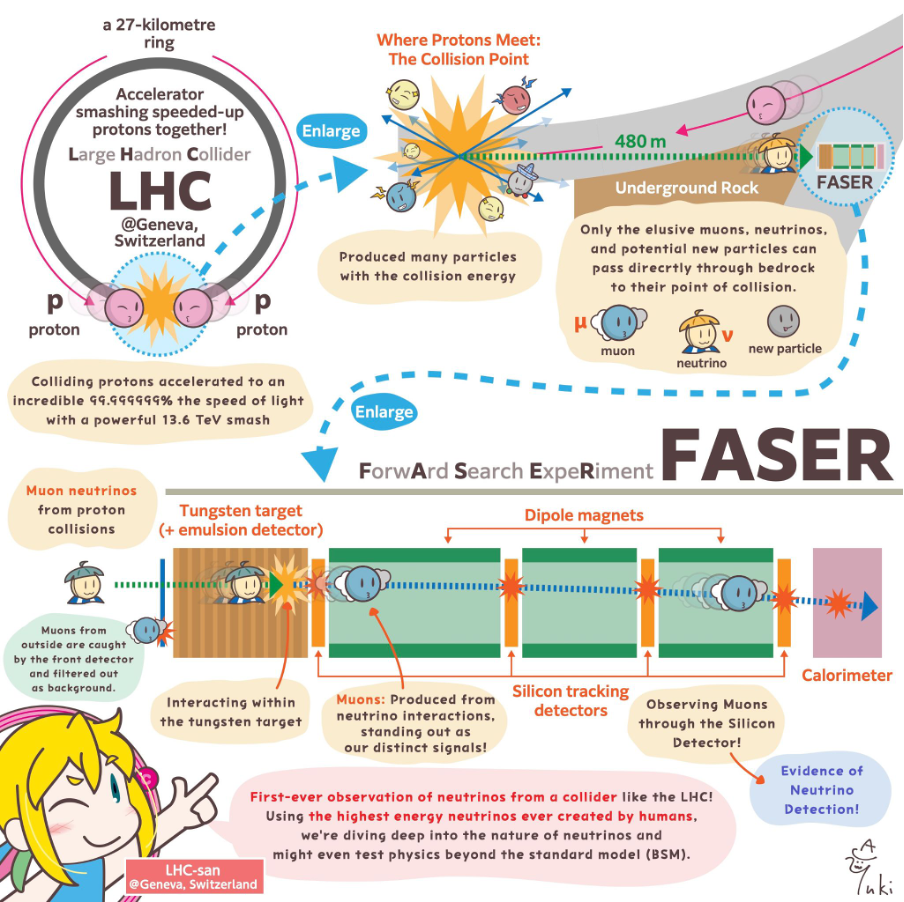

However, there was one source left from which we were not yet able to detect neutrinos: particle collider experiments like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Switzerland. The LHC is the biggest and most powerful particle physics experiment built to date. It collides counter-rotating beams of protons which are accelerated to almost the speed of light and energies that are more than six-thousand times higher than the proton mass itself. These energies are so high that we can produce heavy particles, like the Higgs boson which the LHC discovered in 2012. As a by-product, these collisions also produce a large number of the highest energy neutrinos made by human kind. This makes them an interesting target for scientists.

The most energetic neutrinos are produced in the so-called forward direction, so parallel to the colliding proton beams. Unfortunately, this region is not covered by the conventional LHC detectors. This is where FASER comes into play. Positioned directly into the LHC's neutrino beam, but behind a thick layer of rock that shields it from various other particles, it is in an ideal location to observe neutrinos.

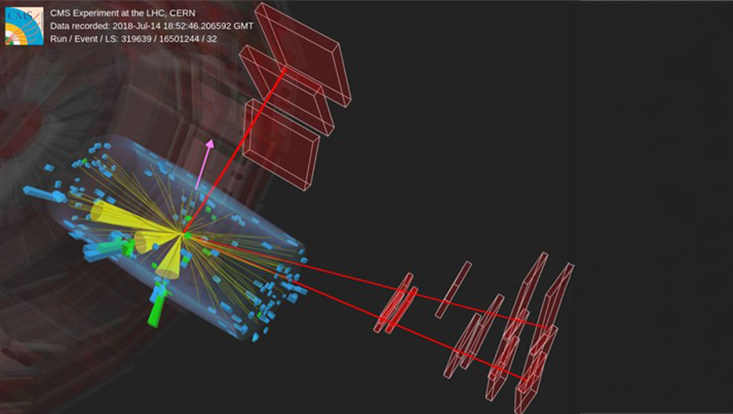

When neutrinos interact with FASER, they typically produce a spray of particles which often includes a muon (which is like an electron, just two-thousand times heavier). Such muon would then pass through the remaining FASER detector, leaving a distinct signal. Careful studies showed that no other known process is able to mimic this signal. After carefully analyzing data collected over several months in 2022, the researchers identified 153 events consistent with neutrino interactions. This observation marks the first-ever detection of neutrinos from a particle collider.

But why is this discovery so significant? Beyond the excitement of observing particles in a new way, this discovery also opens the door to a future program of neutrino physics measurements at the LHC. By studying these measurements, scientists hope to better understand how neutrinos behave at such high energies and even search for signs of new physics beyond our current understanding. Who knows what other secrets await discovery through this new experimental window? The possibilities are as vast and mysterious as the cosmos itself.

About the FASER experiment

Yuki Akimoto@higgstan.com