Another Step towards a Storage Ring-based Gravitational Wave Observatory

24 September 2024

Photo: Schmirander, T. et al. (2024)

In a unique collaboration of the Hamburg Observatory and the Institute of Experimental Physics of the University of Hamburg, which was fostered by the Quantum Universe Cluster of Excellence, a feasibility study of a millihertz gravitational wave detector based on a storage ring has recently been published as a research paper. By proposing to measure the bending and stretching of spacetime using the time-of-flight signal of a circulating chain of heavy ions, researchers of the University of Hamburg may have found a key element to help answer some of the most fundamental astrophysical questions with a novel Earth-based detection principle of gravitational waves.

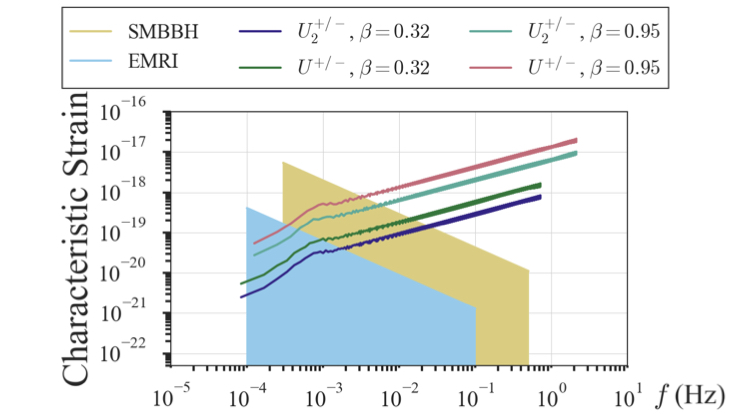

Measuring the gravitational wave signals from the inspiral, ringdown and merging phases of super-massive binary black holes or extreme mass-ratio inspirals is one of the great astrophysical research challenges of our time. A detection of these gravitational waves would allow us to measure the masses and spins of super-massive black holes, and provide us with insights into strong-field effects of general relativity and early galaxy formation. In response to this challenge, the European Space Agency (ESA) is currently developing the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA). LISA is planned to be operational by the next decade, and it will be the first gravitational wave detector to cover the millihertz frequency regime. Existing ground-based gravitational wave detectors, such as pulsar timing arrays and laser interferometers, are sensitive to very low frequencies and to frequencies of tens to hundreds of Hertz, respectively, but leave a sensitivity gap in the millihertz regime in which super-massive binary black holes and other exciting astrophysical sources are expected to emit.

A Ph.D. project within Quantum Universe had previously already established that the velocity of a particle traveling on a circular orbit, such as an ion in a storage ring, depends linearly on the strain of any passing gravitational wave. It was hence concluded that a storage ring could in principle serve as an Earth-based observatory for millihertz gravitational waves by means of a relatively straightforward time-of-flight measurement.

Now, in a follow-up project within the Quantum Universe Cluster of Excellence, another piece of the puzzle for building a detector based on this principle was added by addressing a fundamental challenge. “As any accelerated charge, circulating ions radiate off energy in the form of photons, which carry momentum and therefore lead to noise in the circulation times of the ions,” explains Dr. Thorben Schmirander, a postdoc at the University of Hamburg and lead author of the new study. “Essentially, we wanted to figure out whether the photon shot noise from this so-called synchrotron radiation is a show-stopper for a storage ring gravitational wave observatory,” adds Prof. Florian Grüner, professor of accelerator physics at University of Hamburg.

Fortunately, the researchers were able to identify an experimental configuration in which the signal from millihertz gravitational waves should still be detectable despite the inevitable noise from synchrotron radiation. By using detailed simulations they were able to show that a chain of singly-charged uranium ions or diuranium molecular ions circulating in a storage ring with a circumference similar to that of the Large Hadron Collider would do the trick. This storage ring should be operated without energy restoration by a radio-frequency cavity in order not to impede the free fall of the particles in the longitudinal direction. Prof. Wolfgang Hillert, professor of accelerator physics at University of Hamburg comments: “Our experimental configuration convincingly shows the robustness and potential of this concept.” The researchers predicted that this setup would open up the gravitational wave frequency window of 10−4 − 10-2 Hz.

“These results are very encouraging,” says Prof. Jochen Liske, professor of observational astronomy at the University of Hamburg. “While many challenges remain, this study was an important step towards realising the exciting prospect of measuring gravitational waves from super-massive binary black holes using an Earth-based storage ring as a detector, possibly even ahead of LISA.” The group will now continue to develop this concept by investigating other potential noise sources and developing technological solutions.